Misoprostol: Toxicity or Liberation?

In the first of two blogs about the Reproductive Justice network of the Edinburgh Centre for Medical Anthropology, GENDER.ED’s Undergraduate Intern, Mouna Chatt reflects on a seminar by Cordelia Freeman from the University of Exeter, exploring the biography of the abortion pill, misoprostol.

On 19 March 2025, Senior Lecturer in Geography at the University of Exeter, Cordelia Freeman, presented some of her research on abortion and reproductive justice in Latin America, exploring the abortion pill misoprostol’s possibilities for reproductive justice as part of the Edinburgh Centre for Medical Anthropology’s vibrant Reproductive Justice network seminar series.

Biography of Misoprostol

Freeman started by outlining the history and biography of misoprostol, which was initially developed as a pill to treat stomach ulcers. Dven if it was not a particularly effective medication for stomach ulcers, it was stable and cheap, and therefore continued to serve its purpose. Yet, in the late 1980s, Brazilian activists noticed a ‘warning label’ on the packaging of misoprostol, indicating that it could cause miscarriages. They began self-experimenting with the pill as an instrument to induce abortions. Through this example, Freeman urged us to remember that the notion of ‘toxicity’ is always context dependent. Something that was labelled ‘toxic’, potentially became a source of liberation for some women. She referred to this as a ‘domestication’ of the toxicity of misoprostol.

While Freeman highlighted that misoprostol is often described as ‘magic’ and ‘wonderful’, the pill’s chemical properties, in and of themselves, are not magic. The chemical properties alone would never have been amazing if self-managed abortion activists did not go through self-experimenting processes. Thus, she encouraged us to reflect on and remember the various forms of labour and activism that have made misoprostol a ‘wonderful’ or ‘magic’ pill.

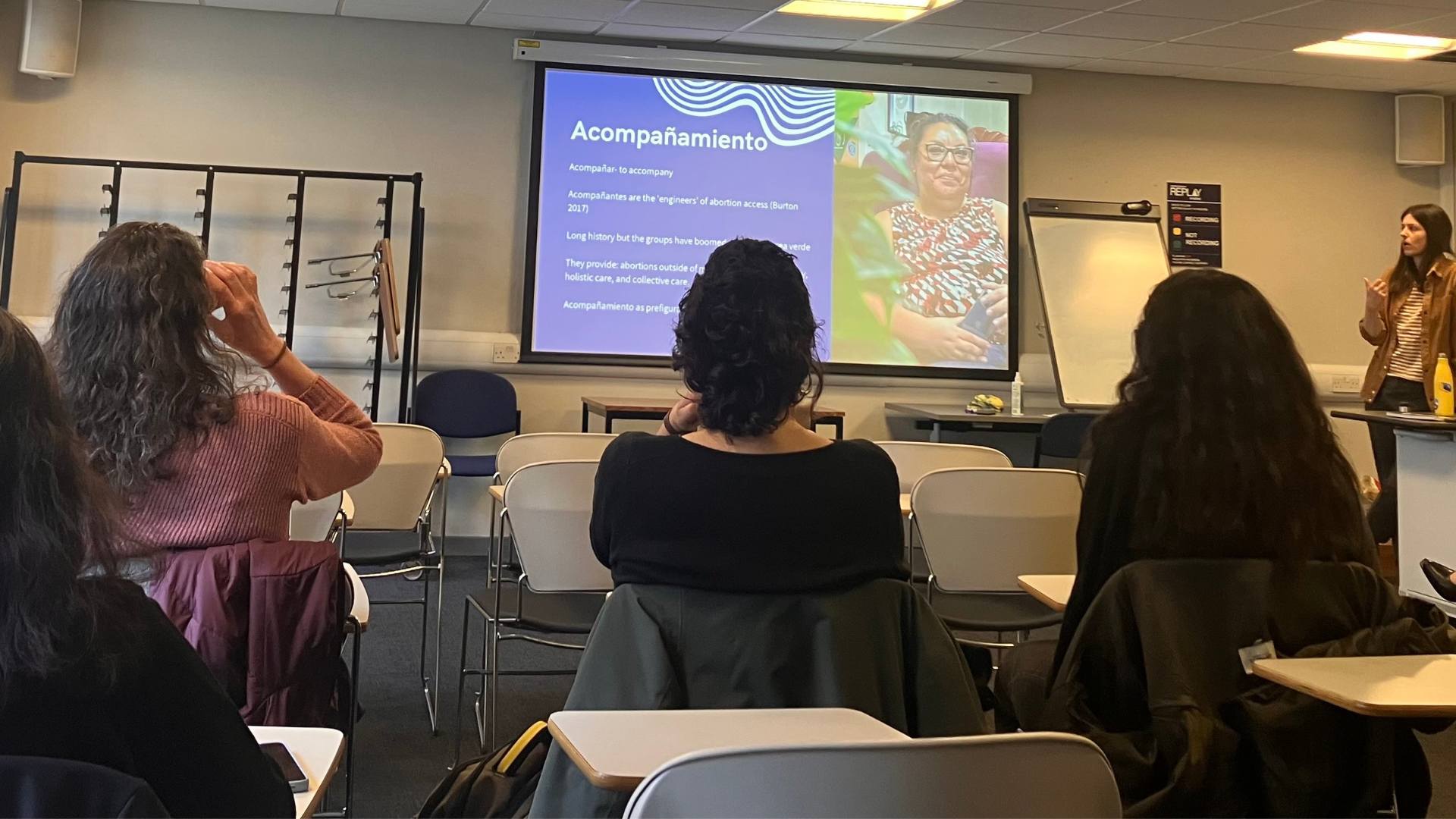

Accompañamientos

Freeman then discussed the practice of accompañamiento activists and activist groups, which operate across Latin America to ‘accompany’ women through their abortions. There are various accompañamiento groups with differing, context-specific histories across Latin America, but Freeman showed that they all have four things in common. First, they support people to have abortions outside the medical context. However, this does not mean that they blanket-reject medical practice. In fact, some of them are doctors themselves, or build networks with friendly medical professionals to aid them in their activism. Second, they all centre the concept of autonomy in their praxis. They grant people the agency to decide how they want their abortion conducted. Third, they support abortions that are holistic, meaning that it is not only a matter of giving someone the pill. Instead, accompañamientes also engage with questions like: Does the person having the abortion need emotional support? Might their family need support through the abortion? Fourth, they approach abortions as a form of collective care, asserting, ‘I’m not gonna let someone do this alone’. However, they grant the person having the abortion the autonomy to decide how they want the accompañamientes to be there for them. Is it, for example, by being with them in person? Or is it by sending them regular messages on WhatsApp throughout the process?

After this, Freeman ran through the intricate web of mobilities and strategies that are needed to access and distribute misoprostol. While it is readily available, it still requires a prescription, so activists have come up with a myriad of ways to ensure they can access and distribute it. For instance, some self-managed abortion activists build networks with labs and pharmaceutical companies to ensure that they can continue to access the pill. Other activists bring the pills from outside their respective countries. Freeman highlighted that Peru is now considered a paradiso de miso (a miso[prostol] paradise) in Latin America, which is interesting, because activists had to bring it into Peru from Brazil in the 1990s.

She also showed how some activists will ship misoprostol pills, camouflaged in other trinkets, to people in need of them to make sure that they do not get caught by their families. However, Freeman emphasised that the pills themselves are insufficient. Activists also work to distribute knowledge on how to take the pills, as they are rather unusual. They do this knowledge sharing through pamphlets and handbooks, but also through telephone hotlines.

Freeman’s talk was followed by a fascinating Q&A session, with questions from the audience about her non-academic work on reproductive justice, counter activism that self-managed abortion activists encounter in Latin America, and the relationships between plants that can induce abortions and misoprostol. I found it interested that a ‘hybrid model’ is now developing in Latin America, where, as Freeman highlighted, abortion plants are being used together with misoprostol. Oftentimes these plants are used to reduce swelling and pain. Yet, she highlighted that they mark a return to safe ancestral methods of carrying out abortions together with misoprostol.

You can read more about Cordelia Freeman’s work here and in her forthcoming book with Bristol University Press, Magic Misoprostol: Reproductive Justice and Abortion Liberation in Latin America.

Thank you to the Reproductive Justice network of EdCMA, for hosting this event!