What we talk about when we talk about the environment

Our ECR Spotlight series continues, now with posts that were produced through the Academic Writing for the Public workshops conducted by GENDER.ED annually to develop writing on gender and sexualities for broader publics. In this piece, IASH Fellow Dr Marika Ceschia argues that, in order to go beyond what is being dubbed across the Environmental Humanities ‘a crisis of the imagination’, we need to engage with what she calls a ‘Black maternal grammar’.

What’s the maternal got to do with climate crisis? Apparently, nothing and yet, as I will argue, everything. Thinking with Black feminist theory reveals that the erasure of the Black maternal is at the basis of a dominant order based upon the exploitation of natural resources. To change how we talk about the environment and how we approach climate crisis, we need to rethink our relation to the environment through what I have termed a Black maternal grammar.

While in recent years there has been an increased awareness of climate crisis, we still seem unable to bring into being more just and sustainable futures, as current headlines around what the Guardian has termed ‘The Age of Extinction’ demonstrate. To be able to imagine other worlds, I argue that we must engage and rethink the underlying structures that guide the meaning-making process and that are predicated upon the erasure of the Black maternal. Reading with Black feminist theory allows us to challenge this foundational erasure while rethinking racial, gender and environmental issues.

A crisis of the imagination

Many Environmental Humanities scholars often tend to stress the need for new narratives: framing the climate crisis as a narrative and linguistic conundrum to be addressed with the help of the literary imagination, Lawrence Buell, Isabel Pérez-Ramos, Matthew Schneider-Mayerson, Marco Armiero, David Pellow, Stefania Barca, Glenn A. Albrecht, Rebecca Solnit and others have argued for an ‘ecotopian lexicon’ and searched for ‘new’ or ‘counter-narratives.’

While I concur with the framing of the current climate crisis as profoundly linked to a crisis of the imagination that can benefit from an engagement with alternative narratives, I want to suggest that we must employ the narrative imaginaries of Black women’s writings to critically re-examine the structures, which I call grammar, that underlie and order the dominant meaning-making process. If we merely search for and uncover new stories and new words without changing the underlying rules that regulate how narratives acquire meaning and how we read them, we can only go so far. We need to uncover and reassess the norms and rules that guide how stories achieve meaning. Until we tackle this issue, we will not be able to imagine, let alone bring into being, visions of alternative worlds.

The maternal provides a productive lens with which to read those grammars underpinning the construction of race. As Jennifer C. Nash has argued, racial ideology depends upon a failure to imagine the Black maternal ‘as life-giving.’ Linking this illegibility to the plantation, Hortense Spillers has underlined how the brutal antiblack grammar of slavery resignified the maternal as a praxis for capital accumulation and tethered it to what Orlando Patterson has termed ‘social death.’ But it is through Black women’s grammars and their signifying praxes that the maternal becomes legible as the nurturing of Black social life. How does this insurgent maternal practice of Black social life translate into a Black ecology with which to perform alternative modes of reading nature? To answer this question, I have found provocative and instructive to turn to the work of Alexis Pauline Gumbs, who explores ecology via a Black feminist lens.

A Black maternal grammar for the future

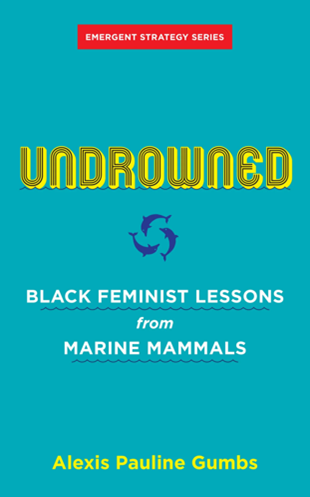

Image credit: Herb Thornby

In Undrowned (2020), which she defines as her ‘pragmatic course of study,’ ‘queer Black feminist love evangelist’ Alexis Pauline Gumbs performs a maternal grammar that enables her to ‘rethink and refeel’ her relation to the non-human other in aural terms, escaping dominant ocularcentric modes of knowledge. She places this ‘Marine Mammal Apprenticeship’[1] within a maternal legacy: ‘my grandmother Lydia Gumbs got a message from some Atlantic bottlenose dolphins too, they inspired her design of the revolutionary flag, seal, and insignia of Anguilla: three bottlenose dolphins swimming in a circle […] And though the revolution was short-lived, our listening continues.’ For Gumbs, unlearning colonialist ecologies and performing alternative modes of relating to the other starts from a reimagination of the maternal. Beginning each section with a three-dolphin maternal sign that recurs throughout the book like a maternal refrain, and reinventing the oral skills of her grandmother, through her writing Gumbs performs a maternal grammar. In her textual praxis, this grammar forms the basis of a decolonial mode of being and inhabiting the Earth based upon a thinking with, rather than about, that enables the non-human other to become an active participant in processes of knowledge-making.

Engaging with Black women’s maternal grammars as theorized in their creative works, will allow us to decolonize dominant modes of meaning-making and rethink our relationship with the human and non-human other. The maternal grammar theorized by Black women’s literature offers an invaluable decolonial framework with which to learn to read nature anew, rendering imaginable ‘ecosophies’ of care. Achieving proficiency in this alternative grammar is the key to unthink what is being dubbed, across multiple disciplines, an ‘imaginative failure’ to conceptualize and bring into being alternative futures.

Dr Marika Ceschia is a former postdoctoral fellow at the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Edinburgh, where she has started working on a new project on decolonizing nature writing. Her first academic monograph, Otherworldly Mothering (2024) is published by Louisiana State University Press.

[1] Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Undrowned, 7, original italics